Social Practice

Oct 24 – 31, 2016

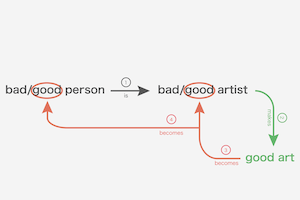

Is art good? Social practice is construed to be good art. It affirms a model of art-life integration where the traditional spaces, contexts, and names of art are identified as exclusionary impediments, and through direct engagement with people, permit individual and social change, rather than merely a mediated zone apart where power and credit (both symbolic and material) are concentrated. In de-emphasizing mediation, social practice identifies the art object as an obstacle to the transformative power of art, proposing instead a form of connection and collaboration with the world that is holistic, viable, and progressive.

The one object on display and which gives the show its name is titled Social Practice. This object is designed to address a particular problem of project spaces operating in economically depressed or underserved neighborhoods, which is that they contribute to impending socioeconomic change, and act intentionally or not, as potential catalysts for that neighborhood’s eventual gentrification. Social Practice is a drawing documenting a walk around four corners of the block surrounding the project space, where the artist contributes to the preservation of the character of the gallery’s neighborhood through an infusion of cash into local businesses. The conceptual parameters of the work stipulate that any proceeds from a potential sale of the work would then go to expanding the area by which the action could be potentially reenacted, generating another drawing to document it, the sale of which will generate another walk and another drawing ad-infinitum. The object on display attempts to negotiate the guilt of gentrification while hinting at something more pervasively problematic in the larger culture— that one can reliably spend their way out of a problem.

To further express his creeping skepticism about art’s capacity for goodness, the artist has made his bodily self as a site for gender identity experimentation, both as an appropriation game with autobiographical reference to another well-known Leclery (a drag performer in Cologne), and as a mode of therapeutic integration towards personal growth. Would this be an insensitive form of cultural appropriation lacking in personal responsibility to the language or culture that the artist is appropriating—appearing as a contorted representation—or would it be clear that the artist identifies as someone negotiating their gender identity?

Within the space a conflation of the artist and “art”—as an essentialized construct, animated with something comparable to human agency occurs, in which both artist and art vie for attention and validation with unabashed, genuflective immodesty. By using what could be considered the architecture of art, or rather the arbitrary spaces in which a particular exhibition has been scheduled to occur in—and/or the proposed event of art to integrate art and life more thoroughly, the artist attempts to use life, to help art help his life. This desire to integrate art and life derives, in part, from the observation that there’s meaningful yet arbitrary criteria for art and if they are integrated, then perhaps the artist’s life could have meaningful arbitrary criteria as well. That redemptive dimension is a plea in some ways for art to help the artist’s life—not only to justify the artist’s sense of entitlement, but to say that “Diego too is good!”